Hiding The Devil In The Details: Beyond Low-Carb vs. Low-Fat and Heart Disease

- Andrew Kowalski

- 2 days ago

- 8 min read

Andrew Kowalski, MD, FASN

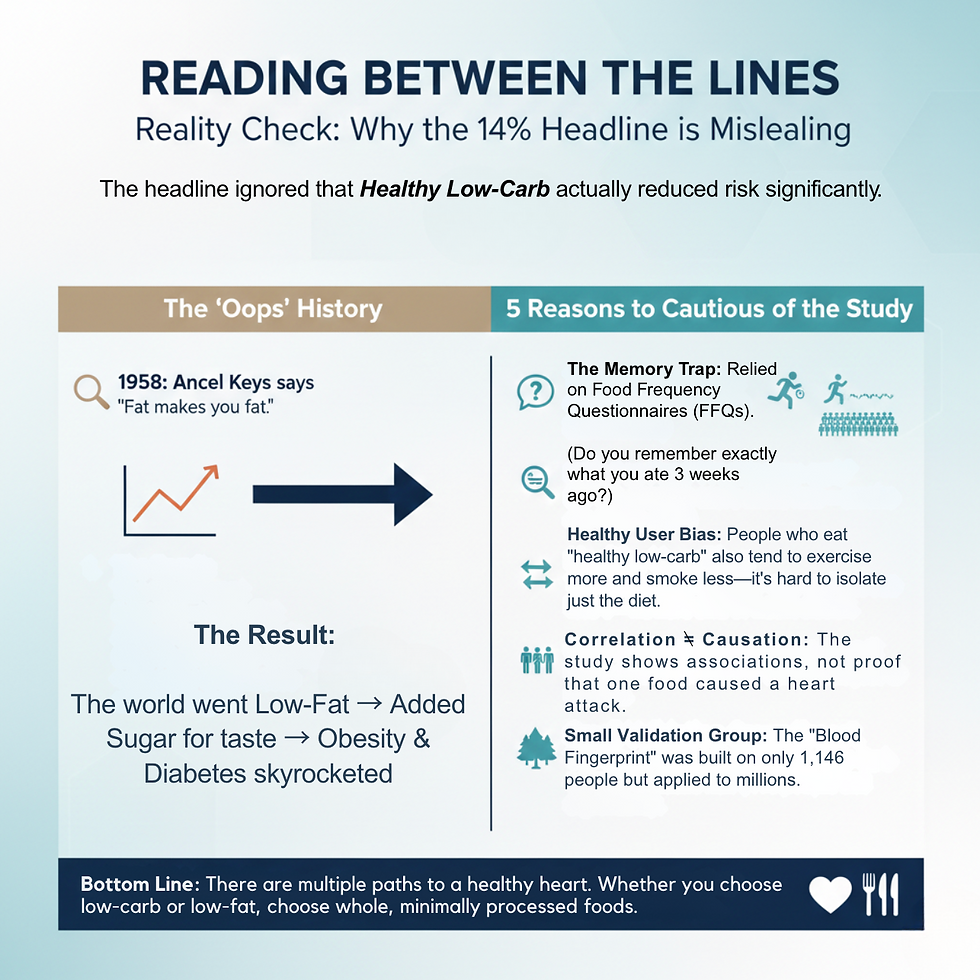

A recent publication by JACC (Journal of the American College of Cardiology) has already made headlines among popular magazines like National Geographic. What caught my attention is that the interpretation of the study suggested that a low-carb diet contributes to a 14% increase in heart disease!

Of course seeing this headline caught me by surprise and made me wonder what was found that influenced this story. In 1958 the dietary world was thrown upside down and sideways due to the famous phrase that "Fat makes you fat." Ancel Keys (1904 – 2004) launched the Seven Countries Study (SCS) in 1958, after exploratory research on the relationship between dietary pattern and the prevalence of coronary heart disease in Greece, Italy, Spain, South Africa, Japan, and Finland. Out of all his scientific accomplishment, the SCS is arguably the most important. This sparked a trend that is only now being recognized as an "Oops," to put it lightly. The Fat makes you fat trend exploded the "low-fat" craze, eat less meat and increase your carbohydrate intake. Unfortunately, once this trend took off so did obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Yet no one was really vocal about this coorelation. It seems that despite being on a "low-fat" diet heart disease was not going away, but actually getting worse.

What many consumers didn't realize is that fat is a much needed macronutrient that is the foundation of cell structure, organs and nearly all of our hormones. To take it a step further, low fat foods do not taste very good and to off set the taste and continue to have consumers by these products SUGAR was added in large amounts.

Welcome to the birth of how the western dietary world perfected processing food.

Yet, even now, the headline that low-carb diets contribute to heart disease adds to more uncertainty and confusion among our patients and even healthcare providers (with the hope that they actually read the journal article and not periodicals or just stop at the headlines).

Unfortunately, this long-standing debate between low-carb and low-fat diets for cardiovascular health appears to have no end in sight, and has captured public attention yet again. The study in JACC (Effect of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets on Metabolomic Indices and Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Individuals) is a large prospective analysis spanning three major U.S. cohorts (a group of individuals who share similar characteristics, experiences or traits within a specific time period) may finally help us move past this binary question.

Follow me on this one and I will explain what this study is and what is it NOT. More specifically, how the title is extremely misleading and the only question it answeres is nothing new, BUT THE OBVIOUS. It restats what we already know when time is taken to actually read what it says.

This study, conducted in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), Nurses' Health Study (NHS), and Nurses' Health Study II (NHSII) from roughly 1986 through 2019, examined not just whether people ate low-carb or low-fat diets, but rather the quality of those dietary patterns. Using food-frequency questionnaires (problem number one)...the data comes from what these individuals remember or how honest they chose to be. To score participants on ten different diet patterns (five low-carb variants and five low-fat variants) researchers also distinguished between animal-based, plant-based, healthy, and unhealthy versions of each approach. They went a step further by creating metabolomic biomarker scores from blood metabolites in a validation subsample of 1,146 participants, testing whether these biological signatures tracked coronary heart disease risk similarly to the questionnaire-based dietary scores.

What are “metabolic indices” here?

They mean two kinds of “body chemistry readouts”:

Regular blood markers

Triglycerides (TG)

HDL (“good”) cholesterol

hsCRP (inflammation marker)

Metabolomics score

A single score made from lots of tiny blood chemicals (metabolites).

Think of it like a blood “fingerprint” that tends to show up in people eating a certain pattern.

They mention examples that moved with “healthy” patterns: higher 3-indolepropionic acid and lower valine.

How did they “validate” the questionnaires (FFQs)?

They didn’t prove the FFQ is perfectly accurate. They did something more like a reality check:

People filled out the FFQ → researchers calculated a diet score (low-carb/low-fat, healthy/unhealthy).

In a smaller group, they also measured blood metabolites.

They built a formula that says:“If your blood metabolites look like this, you probably scored high on that diet pattern.” (I'm sure you can start to see the holes in this picture)

Then they checked:

Do the blood-based scores line up with the FFQ scores?

Yes, somewhat (stronger in the small training group, weaker in the big cohorts).

Do the blood-based scores predict heart disease risk in the same direction as the FFQ scores?

Yes, mostly.

What that validation truly means

It supports that the FFQ diet patterns capture a real signal (not pure noise).

It does NOT prove the FFQ is “accurate” for each person.

Also, metabolites reflect diet + metabolism + weight + insulin resistance + meds + microbiome, so the blood score isn’t “diet-only.” Additionally, you might begin to see how in some individuals the score can be completely off when; considering weight, medications and what kind of bacteria live in the gut (antibiotics can really change this).

That’s the whole trick: FFQ → pattern score, and blood metabolites → independent-ish cross-check that the pattern shows up in biology.

Across more than 5.25 million person-years of follow-up, the researchers documented 20,033 coronary heart disease events. When comparing the highest versus lowest adherence to these dietary patterns, the overall low-carb diet showed only a modest 5% higher relative hazard for coronary heart disease, while the overall low-fat diet demonstrated a 7% lower risk.

However, these aggregate numbers mask the real story, which emerges when we examine the quality variations within each dietary approach.

The healthy low-carb pattern was associated with a 15% lower relative hazard

The unhealthy low-carb pattern showed a 14% higher risk (a nearly 30% spread within the same macronutrient world)

Healthy low-fat patterns demonstrated 13% lower risk

Unhealthy versions carried 12% higher risk

Whether participants emphasized animal or plant sources within each pattern also mattered considerably.

Vegetable-based versions consistently outperforming their animal-based counterparts

These findings prove again that plant-based diets containing higher amounts of healthy foods such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and oils (*COUGH* *COUGH* also known as HEALTHY FATS) are associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk

Those including higher amounts of refined grains, potatoes, and foods high in added sugar are linked to increased risk (PubMed)

The metabolomic analysis added another layer confusing infomation to these observations.

Healthy dietary patterns, regardless of whether they were low-carb or low-fat, were linked with favorable metabolic profiles including lower triglycerides, higher HDL cholesterol, and reduced high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

The metabolite signatures also revealed higher levels of 3-indolepropionic acid (IPA), a gut bacteria-derived tryptophan metabolite (associated with cardiovascular health), and lower concentrations of valine (branched-chain amino acid) that has been linked to cardiometabolic risk in multiple cohort studies.

Recent research has identified IPA as the most down-regulated metabolite in patients with coronary artery disease, and prospective studies in patients with established coronary disease have found that higher plasma IPA levels are associated with significantly reduced risks of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality PubMed, PubMed.

Bottom line is Higher levels of IPA = Healthier Heart

On the other side of the metabolic equation, circulating branched-chain amino acids, particularly valine and isoleucine, have been positively associated with incident cardiovascular disease in large prospective cohorts, with meta-analyses showing that elevated isoleucine levels in particular confer approximately 10-15% higher cardiovascular risk independent of traditional risk factors PubMedPubMed.

These findings suggest that healthy eating patterns may influence cardiovascular risk because of key pathways involving gut bacteria metabolism and amino acid handling.

Another important point is that correlations between metabolomic scores and dietary indices were only weak to moderate in the full cohorts (ranging from 0.21 to 0.38), suggesting that blood metabolites capture dietary signals ALONG WITH OTHER FACTORS.

What becomes clear from this article is that the traditional "low-carb versus low-fat" framing misses the forest for the trees.

The largest differences in heart disease risk is not driven by whether someone restricts carbohydrates or fats, but rather the quality of their dietary pattern, whether they're consuming whole versus refined carbohydrates, emphasizing plant versus animal protein sources, obtaining adequate fiber, and choosing unsaturated over saturated fats. This interpretation aligns with earlier research showing that vegetable-based low-carb patterns appear more favorable than animal-based variants. A comprehensive meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies involving nearly 700,000 participants found that the highest adherence to plant-based dietary patterns was associated with 16% lower cardiovascular disease risk and 11% lower coronary heart disease risk, with even stronger protective effects observed when healthy plant foods were specifically emphasized PubMed.

The data suggests that someone following a healthy low-carb approach centered on nuts, seeds, vegetables, and plant proteins may have cardiovascular outcomes quite similar to someone following a healthy low-fat diet rich in whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. Conversely, both unhealthy low-carb diets and processed/refined proteins and unhealthy low-fat diets loaded with refined grains and added sugars appear to carry elevated cardiovascular risk.

That said, several important limitations in the study drop my confidence in these findings and underscore why we should be CAUTIOUS about making overly strong dietary proclamations.

Food-frequency questionnaires, while valuable epidemiological tools, carry measurement error that can blur true effects and introduce bias in unpredictable ways

The "low-carb" and "low-fat" categorizations based on these questionnaires represent somewhat fuzzy exposures, especially when assessed over decades

Confusion and healthy-user bias remain substantial concerns, particularly in groups of health professionals who may differ systematically from the general population

People who successfully adhere to healthy dietary patterns are also more likely to exercise regularly, avoid smoking, maintain preventive healthcare, and practice other health-promoting behaviors that are difficult to fully adjust for statistically

The study compairs ten dietary indices and biomarkers. These scores increase the probability of finding statistically significant but practically small associations, particularly near the null value (meaning the more markers that are checked the higher the chance of finding a correlation).

The metabolomic score was developed in only 1,146 participants, and its acuracy and value when looking at larger cohorts suggest that it is simply a TERRIBLE SCORING SYSTEM. Finally and the most fundamental part of this study is its design, and that it COMPLETELY FAILS to answer questions of causality. This study shows POSSIBLE associations, NOT proof that one dietary approach causes better or worse outcomes.

The safest interpretation of this large body of evidence is neither "low-carb is dangerous" nor "low-fat is superior," but rather that the quality of our dietary choices matters far more than the macronutrient ratios we achieve. Whether someone gravitates toward a lower-carbohydrate or lower-fat approach may be less important than ensuring that approach emphasizes whole, minimally processed foods; includes abundant vegetables and fiber sources; favors plant proteins or lean animal proteins over highly processed meats; and provides healthful fats from sources like nuts, seeds, avocados, and fish rather than saturated fats from processed foods. For patients navigating the confusing landscape of dietary advice, this finding offers a liberating message: multiple dietary paths can lead to cardiovascular health, provided those paths emphasize food quality, variety, and adherence to an overall eating pattern that individuals can sustain over the long term.

References:

Xue H, Chen X, Yu C, et al. Gut Microbially Produced Indole-3-Propionic Acid Inhibits Atherosclerosis by Promoting Reverse Cholesterol Transport and Its Deficiency Is Causally Related to Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. 2022;131(5):404-420. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321253

Li Q, Wang X, Pang J, et al. Associations between plasma tryptophan and indole-3-propionic acid levels and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2022;352:58-65. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.05.007

Tobias DK, Lawler PR, Harada PH, et al. Circulating Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in a Prospective Cohort of US Women. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2018;11(4):e002157. doi:10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002157

Chen Y, Wang Y, Xiang H, et al. Association of circulating branched-chain amino acids with risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2022;350:90-96. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.04.026

Hemler EC, Hu FB. Plant-based diets for cardiovascular disease prevention: all plant foods are not created equal. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2019;21(5):18. doi:10.1007/s11883-019-0779-5

Qian F, Liu G, Hu FB, Bhupathiraju SN, Sun Q. Association Between Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1335-1344. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2195

Baden MY, Liu G, Satija A, et al. Changes in Plant-Based Diet Quality and Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. Circulation. 2019;140(12):979-991. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041014

Comments