Physical Activity and Kidney Function Preservation: Insights from Measured GFR Trajectories

- Andrew Kowalski

- 17 hours ago

- 3 min read

Andrew Kowalski, MD FASN

I have been an advocate for exercise among CKD patients for a long time. Fortunately, there have been numerous publications showing significant benefit among CKD patients. From numerous cardiovascular benefits to evidence that it can help lower chronic inflammation and delay CKD progression. I was excited to see another study looking at physical activity and preserving kidney function.

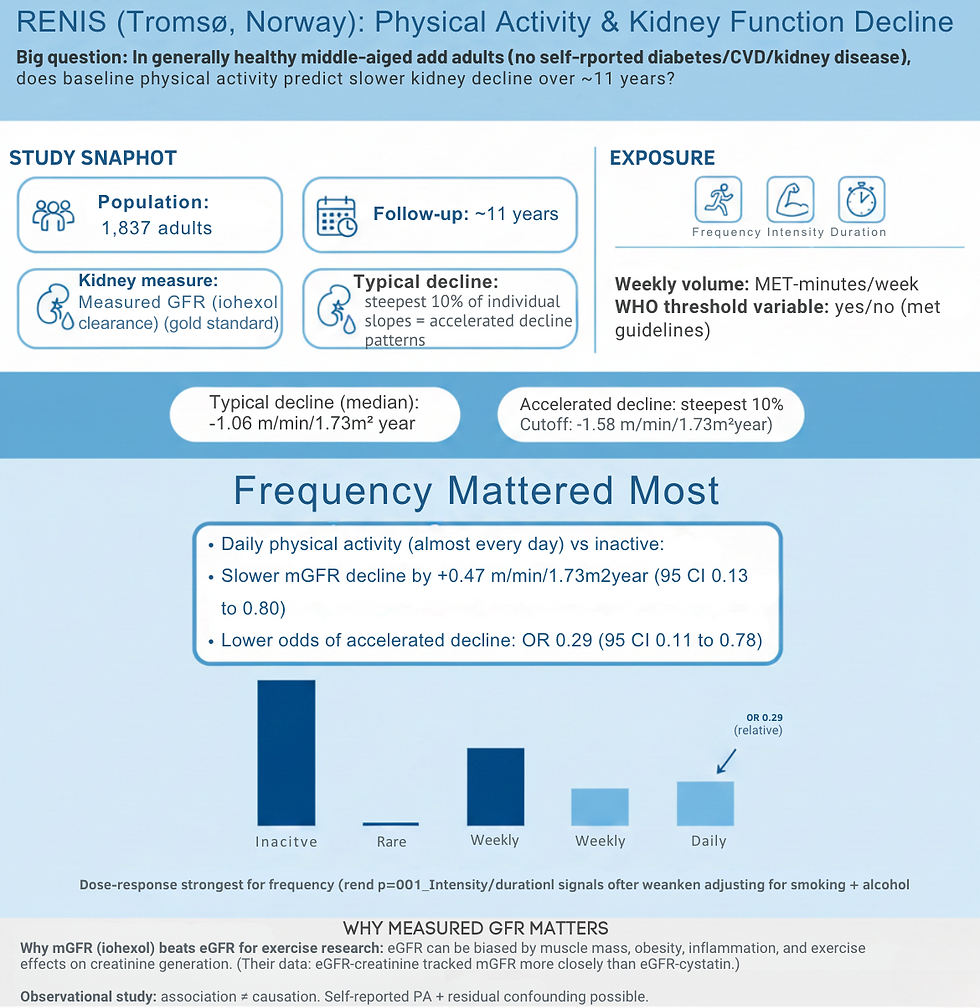

The RENIS study from Tromsø, Northern Norway, asked a clinically relevant question: in a general, middle-aged population without self-reported diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or kidney disease, does baseline physical activity associate with slower kidney function decline over time?

This was a longitudinal investigation. This is a type of research design that involves repeated observations of the same variables (e.g., people) over long periods of time. It is often a type of observational study, although it can also be structured as longitudinal randomized experiment. The researchers followed 1,837 participants with at least one measured GFR assessment (using iohexol clearance) over approximately 11 years, with 1,410 participants having both baseline and follow-up measurements available for analyzing accelerated decline patterns.

Iohexol clearance is a highly accurate, exogenous marker method for measuring the GFR. It is often considered the gold standard in clinical research, including for living kidney donor evaluation. Following intravenous injection, iohexol plasma concentrations are measured over 3-6 hours (often 4 hours) to calculate kidney filtration function, offering a safer, non-radioactive alternative to other tracers.

The researchers assessed physical activity through a validated self-report questionnaire capturing frequency, intensity, and duration, which they measured and created a WHO-threshold variable. They also modeled an annual measured GFR change and then called "accelerated decline" as the steepest 10% of individual slopes (a change of −1.58 ml/min/1.73m²/year or worse). The analysis broken down all possible variables starting with age, sex, BMI, and baseline GFR, then adding systolic blood pressure, blood pressure medications, glucose, and HDL cholesterol, and finally incorporating smoking and alcohol consumption.

Frequency Matters Most

The median measured GFR decline across the cohort was −1.06 ml/min/1.73m²/year. In statistics the median is the middle value in an ordered dataset, representing the 50th percentile where half the data points are lower and half are higher.

Daily physical activity, defined as exercising almost every day, showed a protective association with kidney function trajectory. Compared to inactive participants, those engaging in daily PA experienced slower measured GFR decline by 0.47 ml/min/1.73m²/year (95% CI 0.13 to 0.80) and had substantially lower odds of accelerated decline, with an odds ratio of 0.29 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.78) in the fully adjusted model. Notably, the dose-response signal was strongest and most consistent for PA frequency (trend p≈0.001), whereas associations for intensity, duration, and WHO threshold often attenuated and lost statistical significance after adjusting for smoking and alcohol consumption.

The authors of the study also suggested potential mechanisms through both traditional cardiovascular pathways and direct renal effects. They note that physical activity operates through reduced oxidative stress and inflammation, along with improved endothelial function (the inner lining of the blood vessel responsible for making molecules to relax the vessel, ie Nitric Oxide), but emphasize that the primary pathway may involve improvements in cardiovascular risk factors. One finding that was a surprise was that they observed a pattern consistent with reduced hyperfiltration at baseline and better preservation over time, specifically, more frequent PA was associated with lower baseline GFR but higher follow-up GFR.

Simply put, they noticed that among the individuals that exercised regularly, their kidneys did not work as had and held on to better function for longer! To put is another way, exercise did what many of our new medications do for the kidney, now imagine putting it all together!!

The researchers explicitly discussed WHY measured GFR matters in exercise research, noting that estimated GFR can be systematically biased by muscle mass, obesity, inflammation, and exercise-related effects on creatinine generation, with their data showing that eGFR-creatinine behaved more similarly to measured GFR than eGFR-cystatin.

Or put in another way, using the "tried and true" equation of creatinine and eGFR was similar to the gold standard measurement when checked in individuals that exercise. This also points to the fact that the kidneys in individuals that exercise work differently and do not "burn out" like in those that did not exercise.

Clinical Implications

Several practical takeaways emerge from this work:

Frequency appears to outperform "hero workouts," rather than the intensity or duration of individual sessions.

Daily activity conferred a meaningful preservation benefit: if the 0.47 ml/min/1.73m²/year difference persisted across the 11-year observation period, this translates to approximately 5 ml/min/1.73m² of GFR "saved," though this represents a simplified extrapolation of the annualized rate difference.

Lifestyle behaviors cluster in ways that matter for research and clinical counseling. Smoking and alcohol consumption meaningfully altered effect estimates, acting either as confounders or partial mediators of the PA-kidney relationship.

Comments